As always

This tutorial reuses an application we have built over the different tutorials presented in this website. If you did not read previous installments do not worry: just check out code, read the tutorial and have fun.

In this post we are going to see how to write very readable, high level tests. How readable?

This readable:

Feature: Post management

I can create posts

I can edit posts

I can delete posts

Scenario: Add a post

When I insert a post with title "Foo" and content "bar"

Then I have 1 posts

Then the post has title "Foo"

Then the post has content "bar"

Scenario: Edit the title

Given that on the DB there is a post with UUID=91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 title="Bad title" content="foo bar zum!"

When I edit post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 setting title="Good post"

Then the post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 has title "Good post"

Then the post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 has content "foo bar zum!"

Scenario: Edit the content

Given that on the DB there is a post with UUID=91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 title="Good title" content="foo bar zum!"

When I edit post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 setting content="Foo bar zum! Zum zum!"

Then the post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 has title "Good title"

Then the post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 has content "Foo bar zum! Zum zum!"

Scenario: Delete a post

Given that on the DB there is a post with UUID=91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 title="Bad title" content="foo bar zum!"

When I delete post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622

Then post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 is not found

This is the actual code of our functional tests for posts management: nice, clean and clear enough to support discussions with non-technical people. Now, how do we make this thing work?

We have to take a step back, talk about the definition of functional tests, write some infrastructure code (boring, but we can reuse it across projects) and then finally see how we can define such readable tests.

So, take a breath and let’s get started.

Goal of the functional tests

The terminology for test types is rather confused: different people use the same term to indicate different things and the same kind of tests can be indicated by different names, depending on who you are talking to. In this post we call functional tests those tests which verify, at a high level, that functionalities needed by the user are implemented correctly.

These tests should not check technical implementation details but only the behavior of the application as perceived by the user. Further, they should not consider non-functional features like response time or the load that the application can handle.

Our functional tests should be readable for Project Managers and other stakeholders. In some way they capture functional requirements and help us to verify that those requirements are met.

In this tutorial we will realize functional tests which:

- start the application

- perform some operation (like creating a post)

- verify the results

- shutdown the application

To write these tests we will use Cucumber.

Cucumber

Our functional tests should be declarative and easy to read. For this reason we are going to use Cucumber. Cucumber is a well-known and mature solution oriented to support Behaviour-Driven Development (BDD). It is available for several languages including Ruby and Java. We will use Ruby.

Ruby? Why?

We are going to write are tests using Ruby for two reasons: on one hand Ruby is amazing for writing declarative and concise code and those are very good qualities for our tests. This also effectively enforces a very strong separation between our tests and our application: we are going to interface with the code under tests by running the whole application, not by accessing single classes or methods. Given we are using a different language for tests there is no temptation to sneak in a call to a Java method (no, you are not allowed to do so by using JRuby!).

Anyway, don’t worry, I’m going to hold your hand as we jump into the world of Ruby. Who knows, in the end you might even enjoy it.

Installing Ruby

First of all you need to install Ruby. See this page for instructions.

Once you have done that you can install Cucumber by using gem, the dependencies management tool which comes with Ruby. You can install Cucumber among your system libraries by running:

gem install cucumber

I suggest, however, to use Bundler, a tool which permit to install dependencies locally. Let’s start by creating a directory named functional_tests under the root of the project and then create a file named Gemfile (no extension):

source 'https://rubygems.org'

gem 'cucumber'

gem 'rest-client'

gem 'rspec'

gem 'rspec-expectations'

And let’s make Bundler find the libraries and install them for us:

# to install bundler itself

gem install bundler

# now install everything, locally

bundle install --path vendor/bundle

Plan

Now, writing the functional tests will be fairly simple, but first we have to create some infrastructure. This is where I normally get pretty frustrated. What we need to do is theoretically very simple:

- create a clean database

- run the application with that database

- perform our test steps

- stop the application

- destroy the database

In practice you need all sort of synchronization, because you do not want to start calling your application before it has finished the initialization process or the database is up, right?

I find that in general spawn and manage processes seem to be much simpler and nicer in Ruby, so I am sorry for the ones that did not listen and went on writing their functional tests in Java :)

Infrastructure needed

We are going to run the database in a Docker container because it is a nice way to create a reproducible environment. Ok, we are doing that also to show off a bit. Using a container to run our database we are always sure to start from a given state. We do not persist changes to our container so previous tests run will not pollute the DB. It means that we will always have a fresh copy at disposal for our tests.

If you are not using Linux you have to install Boot2docker. That would mean having to run a couple of extra commands here and there to start Boot2docker.

You should have all the code in the repository, you just need to run this to create the Docker container (think about it as the image of an OS with just your DB installed:

build_docker_container_for_functests.sh

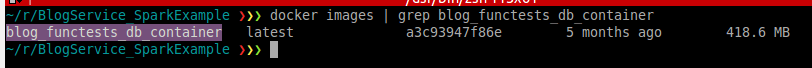

This should create a Docker image named blog_functests_db_container. Let’s double-check that by typing docker images:

What we need to do before and after each test

In our tests we will have to start and stop both the database and the application and we are going to do that for each single test. To do so we are going to write Cucumber hooks.

We create functional_tests/features/support/hooks.rb and write this inside:

#encoding: utf-8

require 'rest-client'

def create_clean_db

started = system 'sh start_db.sh &'

raise Exception.new('Unable to start DB') unless started

attempts_left = 30

while attempts_left > 0

up_and_running = system 'sh db_is_up.sh'

return if up_and_running

puts "Waiting for db... (attemps left #{attempts_left})"

sleep(1)

attempts_left = attempts_left - 1

end

stop_db

raise Exception.new('DB does not respond, giving up')

end

def stop_db

system 'sh kill_all_functests_db_containers.sh'

end

def application_up_and_running?

begin

RestClient.get 'http://localhost:4567/alive'

return true

rescue Exception => e

$stdout.puts "Error #{e}"

return false

end

end

def start_application

res = system 'sh start_application.sh'

attempts_left = 30

while attempts_left > 0

up_and_running = application_up_and_running?

return if up_and_running

$stdout.puts "Waiting for the application... (attemps left #{attempts_left})"

sleep(2)

attempts_left = attempts_left - 1

end

stop_application

raise Exception.new('The application does not respond, giving up')

end

def stop_application

res = system 'sh stop_application.sh'

end

Before do |scenario|

# in case there are leftovers

stop_application

stop_db

create_clean_db

start_application

end

After do |scenario|

stop_application

stop_db

end

So before each test start we ensure that the application is killed, if it was still running (stop_application), and the database is shutdown (stop_db). Note that this should not be necessary but it’s better to be safe than sorry. Then we start the db (create_clean_db) and the application (start_application).

At the end of each test we kill the application and shutdown the database.

Let’s see in more details how we manage the db and the application.

Managing the database

These are the functions we used to manage the DB:

def create_clean_db

started = system 'sh start_db.sh &'

raise Exception.new('Unable to start DB') unless started

attempts_left = 30

while attempts_left > 0

up_and_running = system 'sh db_is_up.sh'

return if up_and_running

puts "Waiting for db... (attemps left #{attempts_left})"

sleep(1)

attempts_left = attempts_left - 1

end

stop_db

raise Exception.new('DB does not respond, giving up')

end

def stop_db

system 'sh kill_all_functests_db_containers.sh'

end

We start the database using the start_db.sh script. It starts Docker in daemon mode and return control to our Ruby function. At that point we have to wait until the database is up and running because otherwise our application would complain and fail.

We do that by calling db_is_up.sh every second for up to 30 seconds, after which we give up.

To check if the database is up we just try to connect to it. This is the content of db_is_up.sh:

psql -h 127.0.0.1 -p 7500 -U blog_owner -d blog -c "select 1;"

Managing the application

This is the code we use to start and stop the application:

def application_up_and_running?

begin

RestClient.get 'http://localhost:4567/alive'

return true

rescue Exception => e

$stdout.puts "Error #{e}"

return false

end

end

def start_application

res = system 'sh start_application.sh'

attempts_left = 30

while attempts_left > 0

up_and_running = application_up_and_running?

return if up_and_running

$stdout.puts "Waiting for the application... (attemps left #{attempts_left})"

sleep(2)

attempts_left = attempts_left - 1

end

stop_application

raise Exception.new('The application does not respond, giving up')

end

def stop_application

res = system 'sh stop_application.sh'

end

We start it by using Maven. start_application_sh looks like this:

mvn -f ../pom.xml exec:java -Dexec.args="--db-port 7500" > log_app_out.txt 2> log_app_err.txt &

echo $! > .saved_pid

We store the content of the output and error streams on file. However, each run of the application overrides the same files (you may want to improve that). We start the application in background (so that the script can terminate) and save the PID identifying their process. Later we use that PID to kill the application.

To verify that the application is up and running we try to contact it on a specific route that we defined for this purpose. That route returns just “ok”, but we use the fact we are getting an answer to recognize when the application is ready to be used (and tested).

Describing the features

After this long and tedious preparation we are ready to write our tests.

Do you remember the nice tests you saw at the beginning of the post? Cool, let’s take a look again at this code (which you should save in functional_tests/features/post_mngt.feature):

#encoding: utf-8

Feature: Post management

I can create posts

I can edit posts

I can delete posts

Scenario: Add a post

When I insert a post with title "Foo" and content "bar"

Then I have 1 posts

Then the post has title "Foo"

Then the post has content "bar"

Scenario: Edit the title

Given that on the DB there is a post with UUID=91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 title="Bad title" content="foo bar zum!"

When I edit post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 setting title="Good post"

Then the post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 has title "Good post"

Then the post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 has content "foo bar zum!"

Scenario: Edit the content

Given that on the DB there is a post with UUID=91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 title="Good title" content="foo bar zum!"

When I edit post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 setting content="Foo bar zum! Zum zum!"

Then the post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 has title "Good title"

Then the post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 has content "Foo bar zum! Zum zum!"

Scenario: Delete a post

Given that on the DB there is a post with UUID=91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 title="Bad title" content="foo bar zum!"

When I delete post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622

Then post 91ff2946-187e-4114-a185-712600ef1622 is not found

The points immediately under Feature are not executed: they are a simple description of what the feature should do. The various elements composing a scenario are instead called steps and they are where the magic happen.

There are three kind of steps:

giventhey represent some preconditions, some initial settings that is expected to prepare the scenariowhenthey represent the operation to be performed and testedthensteps represent conditions to be verified after the operation is performed

Each step is mapped to a Ruby method described in functional_tests/features/step_definitions/post_steps.rb:

#encoding: utf-8

require 'rest-client'

require 'json'

require "rspec"

include RSpec::Matchers

# psql -h 127.0.0.1 -p 7500 -U blog_owner -d blog

def execute_sql(sql_code)

done = system "sh db_execute.sh \"#{sql_code}\""

raise Exception.new("Issue executing sql code: #{sql_code}") unless done

end

#

# Given

#

Given(/^that on the DB there is a post with UUID=([a-f0-9-]+) title="([^"]*)" content="([^"]*)"$/) do |uuid, title, content|

execute_sql("insert into posts(post_uuid, title, content) values ('#{uuid}', '#{title}', '#{content}');")

end

#

# When

#

When(/^I insert a post with title "([^"]*)" and content "([^"]*)"$/) do |title, content|

payload = """

{

\"title\" : \"#{title}\",

\"content\" : \"#{content}\",

\"categories\" : []

}

"""

response = RestClient.post 'http://localhost:4567/posts', payload, :content_type => :json, :accept => :json

expect(response.code).to eq(201)

end

When(/^I edit post ([a-f0-9-]+) setting title="([^"]*)"$/) do |uuid, title|

payload = """

{

\"title\" : \"#{title}\"

}

"""

response = RestClient.put "http://localhost:4567/posts/#{uuid}", payload, :content_type => :json, :accept => :json

expect(response.code).to eq(200)

end

When(/^I edit post ([a-f0-9-]+) setting content="([^"]*)"$/) do |uuid, content|

payload = """

{

\"content\" : \"#{content}\"

}

"""

response = RestClient.put "http://localhost:4567/posts/#{uuid}", payload, :content_type => :json, :accept => :json

expect(response.code).to eq(200)

end

When(/^I delete post ([a-f0-9-]+)$/) do |uuid|

begin

response = RestClient.delete "http://localhost:4567/posts/#{uuid}"

expect(response.code).to eq(200)

rescue RestClient::InternalServerError => e

STDERR.puts (e.methods)

throw e

end

end

#

# Then

#

Then(/^I have (\d+) posts?$/) do |n_posts|

begin

response = RestClient.get 'http://localhost:4567/posts'

expect(response.code).to eq(200)

data = JSON.parse(response.body)

expect(data.count).to eq(n_posts.to_i)

rescue RestClient::InternalServerError => e

STDERR.puts (e.methods)

throw e

end

end

Then(/^the post has title "([^"]*)"$/) do |title|

begin

response = RestClient.get 'http://localhost:4567/posts'

expect(response.code).to eq(200)

data = JSON.parse(response.body)

expect(data[0]["title"]).to eq(title)

rescue RestClient::InternalServerError => e

STDERR.puts (e.methods)

throw e

end

end

Then(/^the post has content "([^"]*)"$/) do |content|

begin

response = RestClient.get 'http://localhost:4567/posts'

expect(response.code).to eq(200)

data = JSON.parse(response.body)

expect(data[0]["content"]).to eq(content)

rescue RestClient::InternalServerError => e

STDERR.puts (e.methods)

throw e

end

end

Then(/^the post ([a-f0-9-]+) has title "([^"]*)"$/) do |uuid, title|

begin

response = RestClient.get "http://localhost:4567/posts/#{uuid}"

expect(response.code).to eq(200)

data = JSON.parse(response.body)

expect(data["title"]).to eq(title)

rescue RestClient::InternalServerError => e

STDERR.puts (e.methods)

throw e

end

end

Then(/^the post ([a-f0-9-]+) has content "([^"]*)"$/) do |uuid, content|

begin

response = RestClient.get "http://localhost:4567/posts/#{uuid}"

expect(response.code).to eq(200)

data = JSON.parse(response.body)

expect(data["content"]).to eq(content)

rescue RestClient::InternalServerError => e

STDERR.puts (e.methods)

throw e

end

end

Then(/^post ([a-f0-9-]+) is not found$/) do |uuid|

begin

response = RestClient.get "http://localhost:4567/posts/#{uuid}"

expect(response.code).to eq(404)

rescue RestClient::ResourceNotFound => e

# good!

rescue RestClient::InternalServerError => e

STDERR.puts (e.methods)

throw e

end

end

Each step method defines a regular expression, for example:

Given(/^that on the DB there is a post with UUID=([a-f0-9-]+) title="([^"]*)" content="([^"]*)"$/) do |uuid, title, content|

This is how we match the steps with the corresponding code. The code is then simply executed.

Let’s see what it does:

- the only

givenstep just insert a post in the DB - the

whensteps perform calls to our web service to create, modify or delete posts - the

thensteps perform calls to our web service to read posts and verify they meet our expectations

Cool, now it is finally time to run our tests.

Run the tests

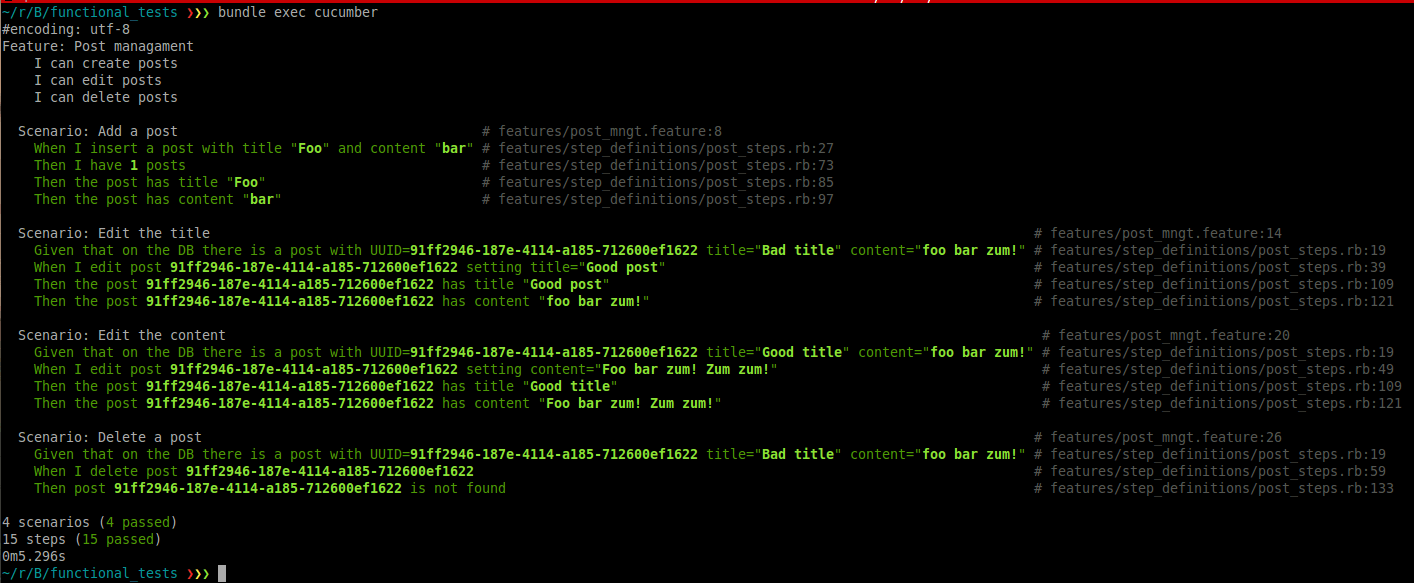

Enter the functional_tests directory and run bundle exec cucumber. You should see a lot of output (our tests are a bit verbose) and in the end something like:

I really like the output produced by Cucumber. And all that green is quite relaxing (we definitely deserve some relaxation at this point!).

Conclusions

I think that functional tests are important because they provide us a guarantee that the application is doing what it’s supposed to do.

There is a lot of room for improvements: it is very important to add proper logging functionalities, so that when something goes wrong we know what’s happened and how to fix it. If our tests fail, we want to understand if it indicates an issue with our application or our testing infrastructure: perhaps someone else is using a certain port or the database was not restarted properly. In such cases we want to find that out without having to tear apart every single piece of our testing infrastructure.

Writing the infrastructure of these tests could take some time (especially to get all the bits right) but the nice thing is that it can be reused across projects.

So, let me just wish you happy testing!